I recently read a post by a friend of mine, Aaron Shyrock called What is Accuracy in Bible Translation?. I want to address some of the concerns that Aaron brought up in regards to accuracy, but I felt that it was first necessary to discuss the meaning of “meaning.” A while ago I wrote a blog that made the claim that all Translation is Meaning-Based. Check out that post if you want to see what I mean by that. As far as I know, Aaron would not disagree with this idea. When we translate (the Bible or anything else) we translate not the words, but the meaning of those words. That might sound strange, maybe even liberal, to you, but I assure you it is not. A word by itself can mean many things. Consider the word “set.” If I just wrote the word “set” in English and asked you to translate it into French (for instance), depending on what sense came to mind, you could use a variety of French words. Consider the word in the below sentences:

- I set the bowl on the table. || J’ai posé le bol sur la table.

- I quit the game after the first set. || J’ai quitté le jeu après le premier set.

- The sun set last night at 6pm. || Le soleil s’est couché hier soir à 18 heures.

- I bought Kaden a train set for Christmas. || J’ai acheté un train ø à Kaden pour Noël.

While in English we have the word “set” that appears in all of these contexts, in French each of these sentences would have a different word. For the last sentence, there is no French word at all that would translate “set.” To make it clear that it was not a real train, you might add the word “toy” into the sentence, but there is no word for “train set” in French. We, then, are not translating the word “set” at all, but rather we are understanding the meaning of the English words, then determining how to communicate that meaning in French. That is the process of translation. All of the words are important, for that is how you understand the meaning. However, you do not translate the words, you translate their meaning. Again, see my other post for more examples.

No one-to-one correspondence between languages

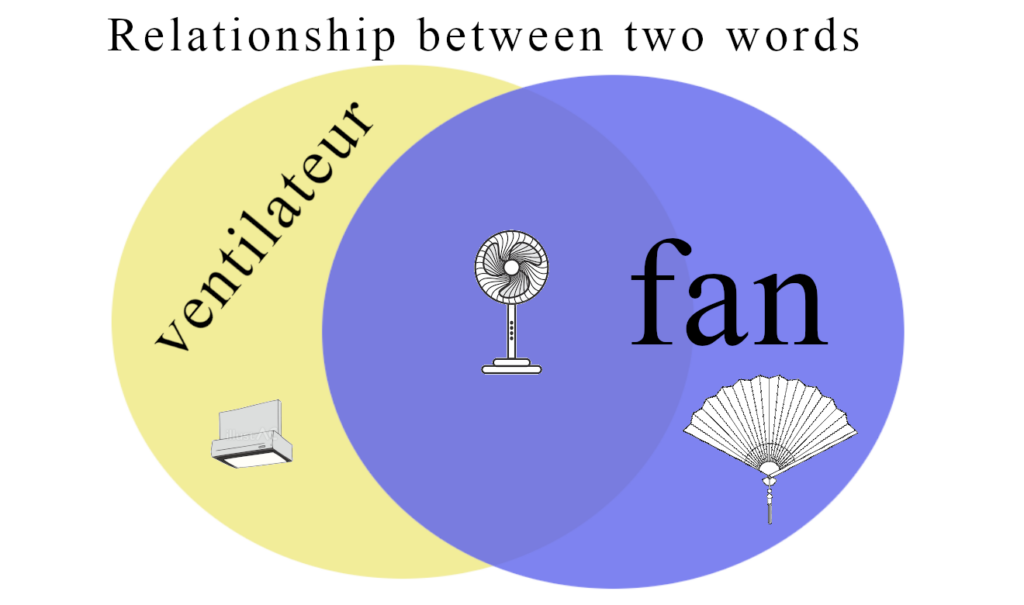

There is a very common misconception in regard to languages. Most people think that there is a one-to-one correspondence between words in different languages. So, for example, we often say things like, “ventilateur” means “fan” in French. While it is not wrong to say that, it is an incomplete way of understanding meaning. In this instance, this blanket statement could lead you to believe that “ventilateur” is the correct translation for the word fan in this sentence: “French ladies often carry a fan in their purse.” I would imagine that you would get a good chuckle if you said that because “ventilateur” is an electric fan, not the kind of fan that you wave in your hand. The correspondence between words in different languages is much more like a Venn Diagram.

The Venn Diagram helps us to see that “fan” (blue) has a broader meaning than “ventilateur” (yellow) because it can refer to a hand fan. Interestingly, what would be called a “ventilator” for a kitchen (also, exhaust fan) would be called a “ventilateur” in French, but a “ventilator” which supports an individual’s breathing, would be called a “respirateur” in French. All that to say, nearly all words have a range of meaning. When translating, you have to find the overlap between words in two languages. Most times, the meaning is not 100% the same. So, a better way to refer to meaning between languages would be to say something like, “In this situation, ‘ventilateur’ would be a good translation of the English word ‘fan'” rather than, “‘ventilateur’ means ‘fan’.”

Discovering meaning via exegesis

A big part of my job is to study each text before we translate and try to understand the meaning. Then, I help my drafting team understand the meaning so that they can translate that meaning into Kwakum. This is harder than you might think. The various books of the Bible were written at different times, some books written thousands of years apart. They were written to different audiences, with different cultures. They were written in different languages. In the Old Testament there are over 400 words that do not exist anywhere else in the Bible in any other form. The precise meaning of some of these words has been lost to time. This is the reason that you can have two different translations of the Bible that are both well-done, faithful, accurate, but also disagree on the meaning of some words. And so, translations differ on the third plague in Egypt (Exodus 8:16): gnats (CSB, ESV, MSG, NASB, NIV, NLT, NRS, DBY, GNT, GW, LEB, RSV), lice (KJV, NKJV, ASV, CEB, CJB, HNV), insects (BBE), sciniphs (RHV).

The hard work of an exegete then, is to seek out the meaning in the text. I have found that when I just read the Bible on my own, or listen to sermons, my mind skips the parts it does not understand well. We, as a translation team, cannot skip those parts. We must translate all of the meaning. So, I must seek to understand the Bible, not just by reading it, but also by reading about the culture, geography, language, etc. that the book was written into.

Re-express meaning via translation

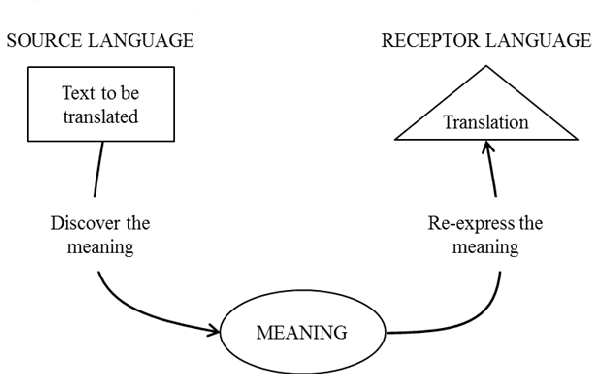

After putting in the effort to discover the meaning, my team then wrestles with how to transfer the meaning into Kwakum. There is a common diagram for translation that I have seen in several books, but I will copy below.

In this diagram, there is a text to be translated (the Bible) which is in a source language (Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek). The process of exegesis is “discovering the meaning,” which is what I discussed above. Once the meaning is discovered it needs to be re-expressed in the receptor language (in this case Kwakum). My drafting team does this orally because I have found that when the Kwakum translators have the text in front of them, they tend to search for one-to-one correspondences. However, when we process it orally, they tend to think in Kwakum, making for a much more natural translation. We then go back and seek to make sure that we did not add, remove, or change meaning.

So here is the rub: how do we know if we translated the meaning accurately? In the case of the French translation of “French ladies often carry a fan in their purse,” you would find out how INaccurate your translation is when people laugh at you. French ladies do not carry electric fans in their purse. You got that one word wrong when you translated it. And the way that you know you got it wrong is by the response of the audience. This is why we have a testing team. My drafting team is always very confident that our translation is accurate. And then, our testing team laughs at us and tells us to go back to the drawing board.

Unlike the conclusion of Aaron’s article, I have found that while meaning in the source text can be discovered apart from the audience, meaning in the receptor language is very audience-dependant. Which means that accuracy cannot be defined, or tested, without knowing one’s audience well and tailoring the translation for that audience. This is blatantly obvious in the most basic of senses: we would not translate the Bible into Dutch for the Kwakum. The audience determines the language of the translation, of course. But the need to examine your audience goes much further than that, as I will discuss in my next post: On Audience. This will be followed by: On Explication. Then I will finally address the issue of accuracy in another post: On Accuracy.1

- image at top taken from: https://www.makeuseof.com/how-to-translate-with-chatgpt/ ↩︎

Thank you for your response to my article. I would love to know what your working definition of “accuracy” might be. My blog post was focused on the definition of accuracy. And what do you think of skopos theory, by the way? How have you translated Genesis 4:4a in Kwakum? Or how would you? Thanks.

Please see forthcoming posts 🙂

I have another example. I was teaching an ESL class and used an online translation program to make a poster in Spanish. It translated the word “party” as “partida.” I was fortunate in that someone pointed out that “partida” refers to, for example, a political party, and is not interchangeable with “fiesta.” I corrected the poster! Thanks for the article.

Another great example, thanks!